International tax rules for multinational companies appear to be approaching a major crossroads, for three reasons. First, the OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) process is increasingly seen as unlikely to deliver on the ambition of its one stated aim, to reduce the misalignment between multinationals’ declared, taxable profits and the location of their real economic activity. Second, the Trump administration and the Republican Congress in the United States is actively considering to break with the entire basis of the OECD approach, which dates back to the 1920s. And third, the continuing failure to include lower-income countries in any serious role in decision-making has made real for the first time the possibility of a UN tax body to challenge the OECD’s hegemony.

And so it’s timely indeed that the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD) is publishing a book on what could well emerge as the new basis for international tax rules over the next decade: the unitary approach. The volume, edited by emeritus professor and TJN senior adviser Sol Picciotto, brings together the findings of a multi-year ICTD research programme involving a group of leading international researchers.

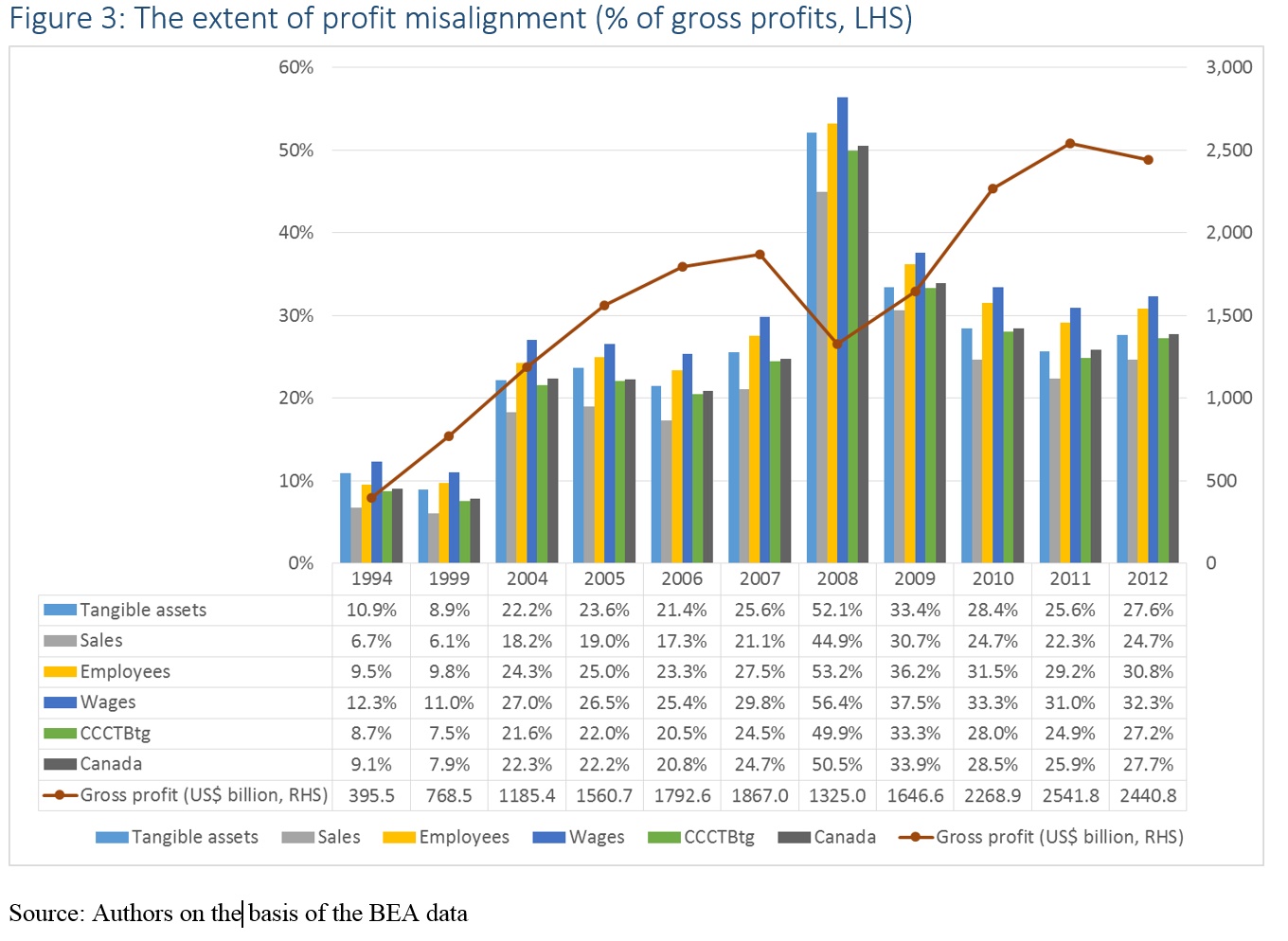

The unitary approach treats multinationals as a single entity, assessing their taxable profits at the global level. This is contrast to the OECD approach, which treats the component entities of a multinational group as individually profit-maximising and taxable. For the OECD, the issue is how to ensure fair market prices (“arm’s length” prices) so that intra-group transactions are not used to shift profits for tax avoidance. This is at odds with the economic rationale for multinationals, that they are more efficient than separate entities trading at arm’s length from one another. And in practice, the complexities are such that alignment of profits with real activity has been impossible to achieve. Our results in chapter 7, for example, show that the ‘misalignment’ of US multinationals’ global profits grew from 5%-10% in the 1990s, to 25%-30% in the most recent data. While this explains why there was so much pressure to initiate the BEPS process, it is hard to reconcile with OECD countries’ insistence on maintaining the arm’s length principle.

In the unitary case, the crucial question is how to apportion global profits between taxing jurisdictions. The answer, on the basis of the consensus view that profits should be aligned with economic activity, is to apportion according to a formula reflecting each jurisdiction’s share of activity. A particularly complex and regressive version of this is the destination-based cashflow tax (DBCFT) proposed by some Republicans in the US. A simpler and more progressive alternative is the formula proposed for use in the EU under the Common Consolidated Corporate Tax Base now being discussed, which reflects not only sales but also assets and employment in each member state.

Defences of the status quo have rested on two main arguments: that the current rules are working, and that unitary tax approaches are too complicated. The first argument is no longer tenable, especially for lower-income countries where the evidence suggests the intensity of revenue losses is greatest. The second argument is largely dismantled by the range of research in this volume. Unitary approaches are seen to be in surprisingly common use already, and with broadly positive results.

Disconnects between policy and research are often frustrating, but sometimes fascinating. In the case of international tax rules, the research contained in the ICTD volume has mapped out a possible future which no longer seems utopian but increasingly achievable. And as the G77 moves ahead with proposals for a genuinely representative global tax body to take over from the OECD, it seems clear that unitary approaches would be high on the agenda. In the meantime, the potential is clear for individual countries and/or regional blocs to introduce unitary approaches. Formulary alternative minimum approaches – in which OECD rules are maintained, but with a minimum threshold for taxable profit based on a unitary assessment – look increasingly attractive. Policymakers and officials will find much of the analysis they need laid out in this volume.