The difficulties of taxing digital TNCs

Taxing Trans-National Corporations (TNCs) that do business through digital platforms is a complex issue for governments. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has been examining the tax challenges of digitalisation of the economy under Action 1 of a global project named Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS). The BEPS project was mandated to the OECD by the G-20 to reform international tax rules.

Current international tax rules were sufficient to regulate the 20th century economy, but the adoption of digital business models by TNCs created the opportunity to operate remotely and derive significant profit without any physical presence. In the current digitalising economy, the rules fail to address fundamental corporate business tax issues such as:

- Who should tax a TNC?

- When should it be taxed?

- How much profit needs to be taxed?

These challenges were highlighted by an OECD report in October 2015. It acknowledged that the whole economy is digitalising, which means that the tax challenges are not isolated to certain sectors. An interim report in March 2018 documented the inadequacy of current international tax regulation, and in 2019 the OECD, through its Inclusive Framework, came up with a policy note followed by a work program to deliver a unified approach to address these problems.

India’s Approach

India has been on the forefront of efforts to address the fundamental issues in taxing digital TNCs. In June 2016, it introduced the ‘equalisation levy’ through the Indian Finance Act 2016. This imposed a withholding tax on payments for digital advertisements made to TNCs by Indian businesses. It was a short-term fiscal measure designed outside the framework of international direct tax architecture. A long-term solution that fits within the architecture was still needed.

Two years later, India introduced the concept of Significant Economic Presence (SEP) through the Indian Finance Act 2018. Under SEP, India proposes to tax digital TNCs who lack a physical presence in India (the litmus test of current international tax rules) based on two alternative threshold elements: the number of users and the amount of revenue generated in India. Once these specified thresholds are exceeded, India will assert its right to tax a digital TNC even where it does not meet the traditional physical presence test.

Having determined that a digital TNC is liable for tax in India, the next big question is the determination of the amount of profit on which it should be taxed. An Indian government committee examined this an April 2019 report. The report proposes a ‘fractional apportionment’ method that would apply if the TNC does not maintain separate accounts that record its branch activities in India in a satisfactory way.

‘Fractional apportionment’ is an approach to dividing up the taxable profits of a TNC in a particular jurisdiction by treating operations within that jurisdiction holistically and thereafter apportion such profits using a formula. This is different to the traditional approach of ‘transfer pricing’, which first carves the TNC up into a group of separate entities, and then determines the profits made by each as they trade with each other and with third parties. It is also different to ‘unitary taxation with formulary apportionment’, because the fractional approach starts with the profits derived from India, rather than the TNC’s global profits. The Indian profits are arrived at by multiplying the TNC’s Indian revenue with its global operating profit margin. For example, if a TNC earns Indian revenue of Rs. 100 million from selling advertisements, and its global profit margin is 5%, the deemed profits from its India sales would be Rs. 5 million. Where the same TNC makes a loss at global level, the global profit margin is deemed at 2%, and Indian profits are estimated to be Rs.2 million.

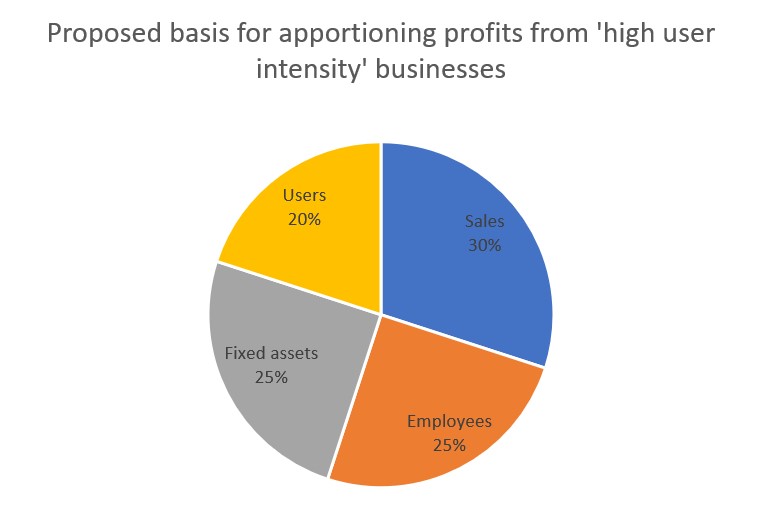

The final step is to apportion this profit between India and the other countries that play a role in generating the TNC’s profits. To do so, a formula based on four ‘allocation keys’ is used: sales, users, assets and employees. The formula is designed to take into account the contribution of ‘supply side’ activities all the way from research and development, as well as ‘demand side’ activities such as marketing and sales. Because the factors are location specific, they can be reliably measured through proper reporting arrangements. The weighting used in the formula was arrived at after reviewing similar regimes used within federal tax systems such as the United States and Canada. The proposed weightings differ depending on the ‘user intensity’ of the business models.

It is relevant to mention that this fractional apportionment method for profit attribution is used only in the case of unincorporated branch operations of TNC. Where the TNC has a subsidiary company in India, this would still be regulated by the single entity principle and transfer pricing rules.

Examination of the Indian policy alternative

The Indian committee’s proposal is an alternative to the ‘authorised OECD approach’ (AoA) for dividing taxable profits between a TNC’s headquarters and its branches using the system of transfer pricing. The AoA was adopted in 2010, in the OECD’s model bilateral tax treaty. The AoA was considered by many to be one-sided, focusing only on supply-side factors. The Indian proposal demands that profit attribution rules should give balanced weighting to both demand and supply side factors. The Indian committee believes that sales could be a reasonable proxy for acknowledgement of demand side contribution to the profits of digital TNCs.

The Indian committee’s proposed profit attribution rules are based on the United Nations model tax convention, which does not follow the OECD’s AoA approach. Most of India’s tax treaties are based on the UN model. India claims to be within its tax treaty obligations and established international precedents to adopt the proposed fractional apportionment rules for taxation of digital TNCs, instead of transfer pricing. Moreover, prior to 2010, the OECD model bilateral treaty also provided for apportionment methods as an alternative mechanism for profit attribution in case of the inadequacy of transfer pricing rules.

However, it is worth noting here that the Indian document continues to adopt the separate entity principle on which transfer pricing is based. It is only in cases where digital TNCs do not keep proper accounts for their branch activities in India that the apportionment method would be used. Subsidiary profit attribution rules would still be governed by transfer pricing rules. This thus raises the question as to whether the Indian proposal is a significant yet inadequate solution to the complex problem of taxation of digital TNCs.

Can the Indian policy alternative work for low-income countries?

India’s emphasis on fractional apportionment as an alternative tax base allocation methodology could be readily adopted by other developing nations. Most of the developing nations have treaties in place which are based on the UN model or the OECD pre-2010 model, and which permit the use of apportionment methods in case of failure of transfer pricing rules. With the emergence of digital TNCs which operate as global unitary firms, the failure of current rules is evident. It is essential to utilize such alternative tax base allocation methods to protect inter-nation equity, until and unless there is a global consensus on a unified and more effective approach.

The need for international tax cooperation

India’s alternative approach to the principles and mechanics for the taxation of digital TNCs creates interesting challenges for consensus building within the OECD’s Inclusive Framework, which is presently the leading multilateral platform for finding global solutions for taxation of digital TNCs. The AoA approach was never likely to become the basis for allocating the tax bases of digital TNCs. It needs revising to account for the contribution of demand side factors, and to use alternative mechanisms of tax base allocation, which reflect the economic reality. India’s position opens the possibility of a strong push to consider apportionment rules as a credible policy alternative for reform of international tax rules under the Inclusive Framework.