There is no scarcity of criticism of the methods that OECD governments have used – and not used – to prevent the spread of the Covid-19 virus. By contrast, the steps they have taken to deal with the economic consequences of the pandemic are more widely appreciated. The OECD now reports regularly on the wide range of measures that governments are taking to counter the three main inter-related economic threats: recession, large-scale company bankruptcies, and the declining incomes of the poor and vulnerable. Tax agencies play a prominent role. Corporate and individual tax obligations have been reduced or deferred on a large scale, and through a wide variety of channels.

Some African governments are already taking similar steps. For example, Kenya recently announced a package of measures including a reduction in the standard rate of corporate income tax and a personal income tax exemption for anyone earning less than 24,000 Kenyan Shillings a month ($226). From the perspective of protecting the incomes of the poor, this exemption looks like very good news. Unfortunately, and not because of any failures on the part of the Kenyan government, it will not benefit many Kenyans. Only 12% of the employed population of Kenya are active payers of personal income tax. The great majority of poor Kenyans do not earn enough to pay it at the best of times. Further, personal income tax coverage in Kenya is actually very high relative to most countries in Africa. In nearby Rwanda, which like Kenya has an unusually effective revenue authority, active payers of personal income tax account for less than 3% of the labour force.

It is very challenging for African governments to use tax measures to counter the economic consequences of the pandemic, and even more challenging to use tax measures to shield the poor.

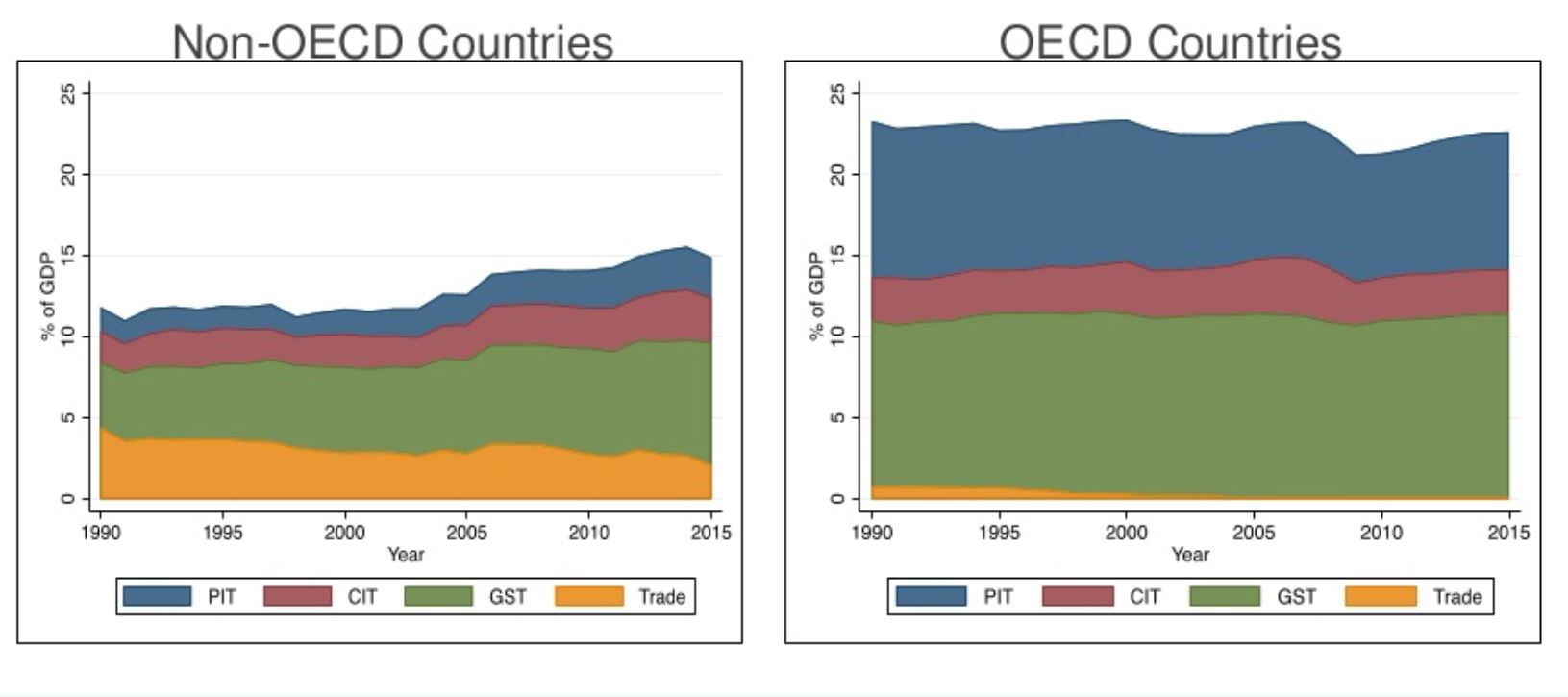

The reasons lie in differences in tax structure between rich and poor countries:

Less fiscal firepower

Governments of rich countries collect through taxes, and then spend, a much higher proportion of GDP (typically at least 30%) than do African governments (typically around 15%). African governments have much less fiscal firepower. If they reduce their tax collections by 10%, they inject only 1.5% of GDP to boost the economy. In rich countries, they inject 3% or more. Similarly, African governments have less scope to re-assign public spending to protect the poor or shield companies from bankruptcy.

Very few Africans pay personal income taxes

The governments of rich countries generally have personal income tax (PIT) records relating to somewhere between a half and nearly all their adult populations, so it is no major challenge to provide a well-targeted income tax refund that can generate an immediate boost to consumption. In most African countries on the other hand, very few people (largely public sector employees and employees of big businesses) pay PIT (blue section in the figure below). So, PIT deferrals or refunds will benefit those who are relatively well-off the most, and are very unlikely to transfer purchasing power to the poor.

The VAT base is much more narrow

Similarly, the proportions of businesses that pay value-added tax (VAT) are much lower in Africa than in rich countries. The main reason is that the business turnover threshold at which companies are required to register for VAT is typically much higher, relative to average incomes. In rich countries, a reduction or suspension of VAT would give a general boost to the economy and directly benefit many small retail outlets and other small businesses. For Africa, similar action on VAT would have less effect, and tend to benefit mainly larger businesses.

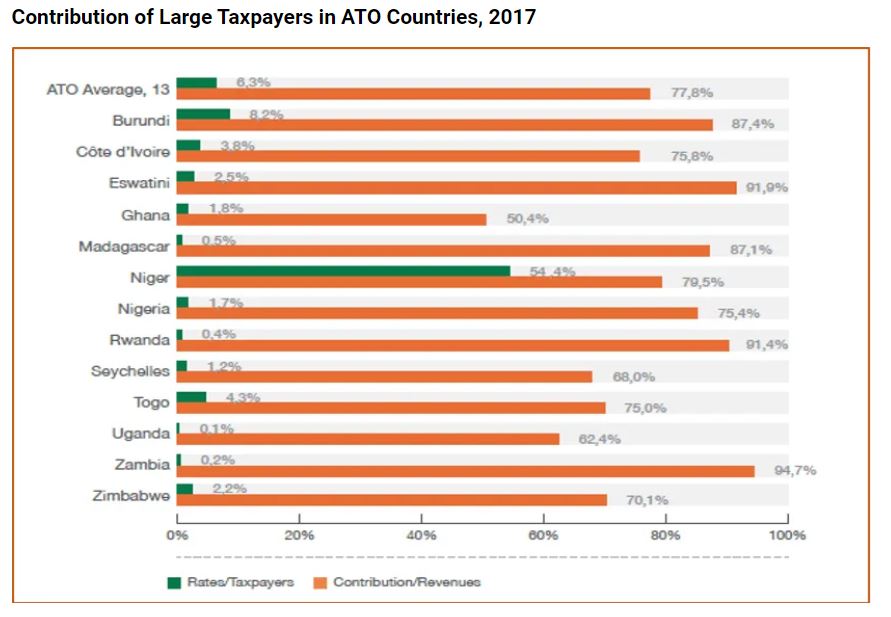

A small number of companies provide the majority of tax revenue

Extremely high proportions of total revenues collected by the governments of many African countries are handed over to them by a small number of large companies. This fact can be expressed in different ways. Take for example the figures from the African Tax Administration Forum’s 2019 African Tax Outlook: On average, the 6% of total taxpayers that were managed by the Large Tax Offices in each country handed over 78% of all taxes collected.

If African governments try to boost their economies through suspending or remitting taxes, the immediate benefits will inevitably flow mainly to large companies. If those companies were at risk of going bankrupt or ceasing to trade, this would be justified. But not all will be at risk. We do not know how far they might spend the additional money, hoard it, or even expatriate it. The banking system will generally be a better means of shielding companies, especially large companies, from bankruptcy.

Conclusions

Based on these differing features of the tax systems in African countries, I have five key takeaway messages:

- Do not expect too much of African tax collectors in this instance. They lack most of the instruments that are available to their OECD counterparts to counter the economic effects of the virus.

- Broad-based cuts to personal and corporate income tax will primarily benefit larger businesses and wealthier individuals, while sacrificing badly-needed revenue. In some cases, an increase in the VAT threshold might benefit small firms, but if possible, more targeted temporary measures such as deadline extensions, payment deferrals, and expediting VAT refunds can help ease cash flow issues.

- Although African tax collectors are ill-equipped to help shield the poor and small enterprises, measures such as waiving taxes on mobile money and on airtime and mobile data can help increase their resilience through remittances and transfers, as well as supporting social distancing.

- Still, tax channels are generally too oblique to safeguard the most vulnerable. If governments have the will and the resources, they will need to step up social protection strategies including cash transfers on a significant scale.

- Looking to the future, the tax collectors and their finance ministers could now begin to think more seriously about their contribution to the post-Covid world. Here they have major roles to play. There will be large public sector debts and deficits to plug. Much more revenue will be needed. That is a challenge, but not an impossible one. There are many sources of revenue that currently under-taxed in low-income countries. The untaxed assets and incomes of the rich should be near the top of the list.

Many thanks to Rhiannon McCluskey, ICTD Research Uptake and Communications Manager, for her contributions to the writing of this piece.