Imagine living in a country where non-state actors provide most basic services instead of the state, natural disasters are frequent, political crises are recurrent, and everyday life is controlled by gangs. Now ask yourself: why would anyone here, let alone the wealthy, agree to pay tax?

That country is Haiti, the poorest country in the Americas, with 60% of its population living below the poverty line. In Haiti, the wealth gap is staggering: the richest 20% own two-thirds of the country’s wealth, while the poorest 20% scrape by with just 1% of resources. Basic services like healthcare, education, and even policing are outsourced to private actors, foreign NGOs, and international organisations. Haiti is therefore known as the “Republic of NGOs”. And then there is endemic violence. Gangs are widespread, with homicides, kidnappings, and sexual violence a horrifyingly commonplace. In February 2024, a gang uprising led by Jimmy “Barbecue” Chérizier plunged the country into chaos. Over 2,500 people were killed, President Ariel Henry was forced to resign, enabling gangs to control 80% of the capital, Port-au-Prince. On top of that, Haiti lives under the constant threat of earthquakes and hurricanes. So why, under all these circumstances would anyone pay tax to a State that has failed them repetitively?

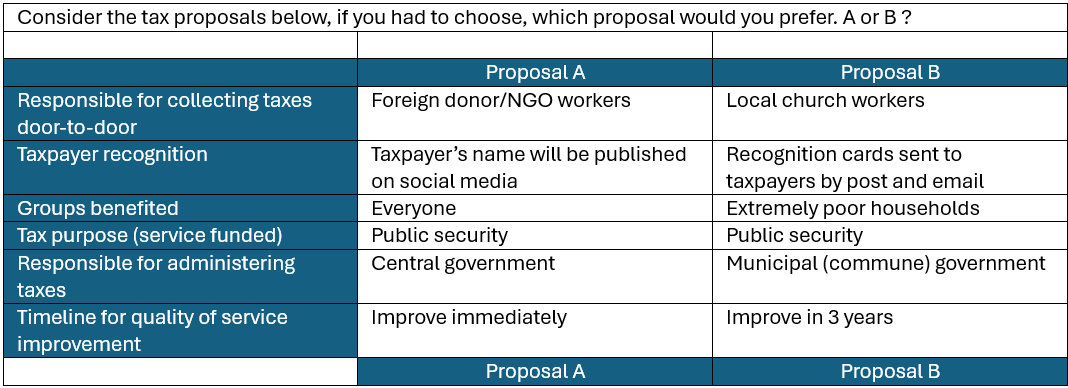

To get to the bottom of this question, we conducted a conjoint experiment in which respondents were asked to choose between various property tax proposals (Table 1). The experiment was included in an online survey with 2,001 Haitians fielded between December 2023 and April 2024. As Haiti was experiencing hyperinflation and a severe food crisis during the survey period, rendering it difficult to obtain reliable and recent estimates of income and/or consumption spending, we decided to rely on the level of education and define as wealthy those with a university degree or higher (a group representing just 1% of the country’s population).

Direct and visible: Why focus on property tax?

In a country where most people work in the informal sector, tracking earnings, and therefore income tax, is near impossible. Value-added tax (VAT)? They are regressive, hitting the poor the hardest and worsening inequality, even though everyone pays the same rate. In Haiti, most people already spend the majority of their income on essential goods such as food and fuel, therefore even a small price hike can galvanise violent pushbacks, exacerbating the country’s cycle of political instability. Take 2017 for example when the government announced tax hikes on fuel, alcohol, and cigarettes, Haitians flooded the streets to protest the rising cost of living.

So, what is left? Property tax. People can’t do much when confronted with property tax, as property is immovable and visible to everyone. And unlike VAT which is hidden in the final price and paid indirectly, property tax is direct. Therefore, when citizens are more aware of taxation, they start asking questions: where is my tax money going? Why do I still feel unsafe in my neighbourhood? All this drives a higher demand for accountability.

For the wealthy, peer approval matters more than public praise

Our research shows how even in the world’s most fragile states, practical measures are available to build support for taxation among the wealthy if policymakers are willing to rethink the meaning of “taxation”. Haiti’s affluent are more willing to support property tax reforms when they receive public recognition for their tax contributions within their local neighbourhoods (e.g. award ceremonies for consistent taxpayers, plaques put up in gated communities). However, broader forms of recognition, like a mention in the newspaper or on social media, are less effective. In unequal societies like Haiti, the wealthy are geographically concentrated and form tight-knit social circles. Therefore, being recognised as law-abiding by one’s community is more valuable than by society at large.

Self-interest is another factor that drives compliance

Even in times of crisis, the wealthy respond out of self-interest. Our study found that support for property tax among the richest in society increases when taxation is pitched as an investment that benefits everyone, not just a handout for the poor or the middle class. Authorities should therefore avoid divisive language (e.g., “tax the rich to help the poor”) or paint taxes as “helping the poor” or “punishing the wealthy.” Investment in “shared” progress is the name of this game and campaigns or slogans that frame tax benefits in such terms are desirable, for example “Taxes build Haiti’s future, and yours.” This strategy would not be perceived as threatening by the wealthy and would actually support broader public good provision.

Unlike foreign NGOs, traditional (religious) leaders understand local communities and command respect

Our experiment revealed something surprising: wealthy Haitians are just as willing to pay tax when collected by government officials working with community and religious leaders as they are when a faceless bureaucrat is responsible. Authorities can thus leverage traditional leaders’ local knowledge and community trust and respect to complement official tax-collection efforts, especially in areas where the state has little reach. In contrast, after February’s gang uprising, trust in foreign NGOs collapsed. Authorities should therefore avoid relying on these entities who are viewed as alien to local communities

Rebuilding trust in local authorities through transparency and accountability

Before gangs took over Port-au-Prince, Haiti’s wealthy preferred property tax to be administered by municipal authorities. But since then, indifference has set in and trust in these local actors has diminished. To counter this, local authorities should rebuild public confidence and promote accountability through measures that increase transparency and citizen engagement. Authorities can use community meetings to explain how tax revenue is used or convene participatory budgeting sessions in which residents voice their concerns.

Haiti does not have the luxury of chasing pie-in-the-sky solutions. It needs something tangible, immediate, and efficient. While property taxation is no magic bullet, it remains a good starting point. Indeed, compliance from the wealthy sends a message of collectivity and increases trust in the (tax) system. In general, greater tax revenue means visibly better public services, which consequently builds trust and strengthens tax compliance. In a country held hostage by armed groups, this cycle could be a game-changer. In contrast, when the wealthy avoid paying their taxes, the State is deprived of the necessary revenue to rebuild, improve security and infrastructure and provide public goods and services, perpetuating a never-ending cycle of violence and poverty. To break this vicious pattern, the State should build tax support among the wealthy through neighbourhood level social recognition, promoting universal redistribution of tax benefits instead of a pro-poor approach, and working with trusted community leaders. Even small wins in the case of Haiti can spark change in the most unlikely of circumstances.