There are now a range of estimates of the global scale of tax avoidance. These include:

- the $600 billion annual tax loss estimated by IMF researchers Crivelli et al. (2015; 2016), which divides roughly into $400 billion of OECD losses and $200 billion elsewhere;

- the $100 billion annual tax losses that UNCTAD’s World Investment Report 2015 estimated for developing countries due only to conduit FDI investment through ‘tax havens’;

- the $100 billion to $240 billion globally that OECD researchers estimate;

- the $130 billion globally that Petr Jansky and I estimated as annual losses due to avoidance by US multinationals only; and so on.

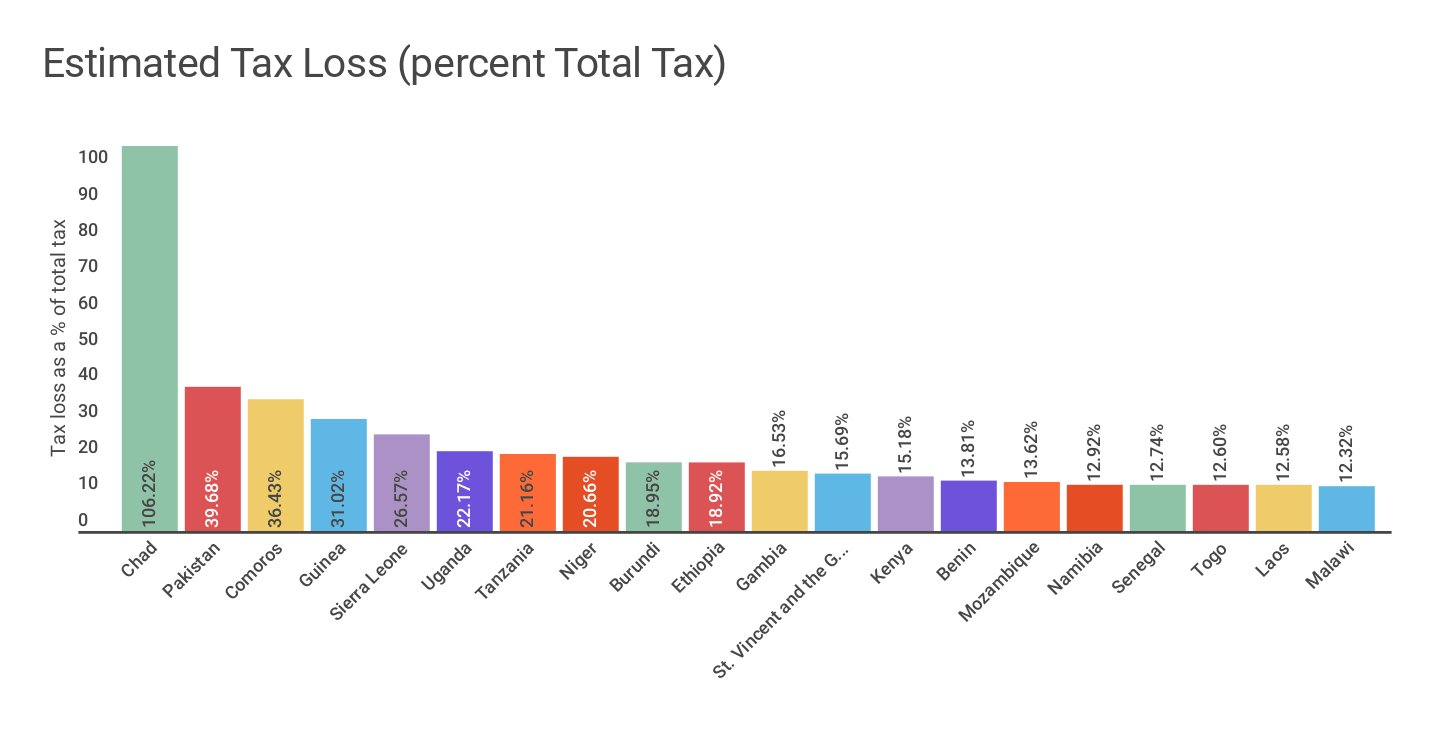

With the exception of the latter, which deals only with multinationals responsible for around 1/5 of global FDI, the estimates have not been broken down to country-level to show the underlying pattern. While the OECD research indicates losses in a range from 4% to 10% of corporate income tax revenues, the IMF researchers’ estimates suggest that OECD countries may lose 2-3% of their total tax revenues, and lower-income countries much more: to 6-13%.

Petr Jansky and I have now reworked the IMF researchers’ estimates to provide the country-level detail, in a paper published by UNU-WIDER today. We chose the IMF paper because it is the only one of the institutional researchers’ efforts to date which has been published in a peer-reviewed journal. The researchers were kind enough to share their code, and we were able to replicate quite closely the original findings. We then revised the results by using the ICTD-WIDER Government Revenue Dataset, which provides significantly better revenue data, and these are our main findings:

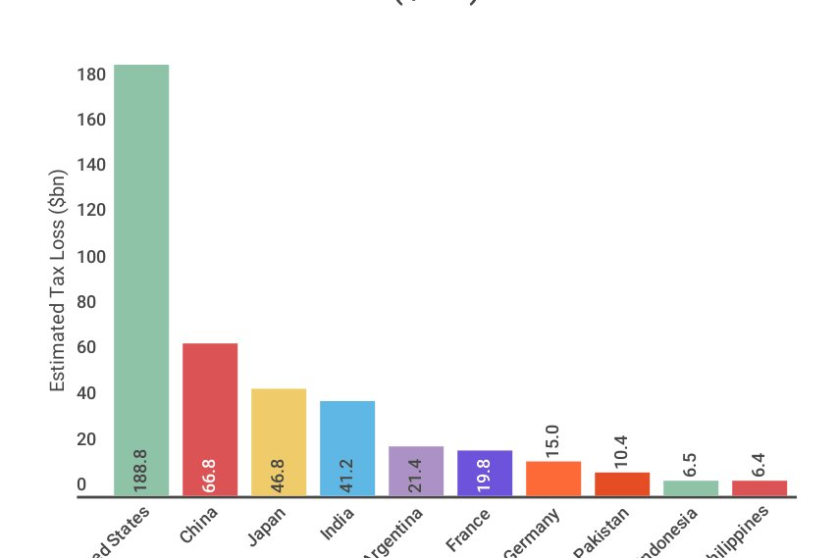

- The global tax losses are estimated at around $500 billion (compared to $600 billion in the original);

- The pattern of greater relative intensity in lower-income countries (measured by losses/GDP or losses/tax revenue) is stronger in our results than in the original; but

- The methodology, and country-level findings, raise a number of questions.

The main questions are three. First, the methodology takes statutory tax rates as the determinant of profit-shifting. The authors do experiment with one set of effective tax rates, and we try with another, but without finding a satisfactory fit. The result is that countries like Luxembourg, with relatively high statutory rates compared to the (often near-zero) effective rates for multinationals, appear to suffer rather than benefit from profit-shifting. Countries with low statutory rates (e.g. in eastern Europe) appear to attract profit-shifting.

Second, looking at country-level results highlights the rather mechanical nature of the model. Once the regression model has determined the sensitivity of taxable profits to the statutory rates elsewhere, the losses in a given country are a simple function of rates and economy size, and so multiple countries are estimated to suffer the same loss as a share of GDP – which is not inherently unreasonable for such estimates, but jars with the intuition that patterns of profit-shifting in practice respond to very particular legal, political and economic conditions.

Third, some of the individual results appear extreme. Does Chad lose more than its actual (non-resource) tax revenue? Perhaps, as resources are dominant. And yet… Does Pakistan lose 40% or so of its tax revenue? The country is known to face extreme tax difficulties, but still… Do a number of countries from Argentina to Zambia lose 4% or more of their GDP? Here’s the thing: if numbers like the IMF’s $600 billion estimate include country-level findings we’re not sure of, these should be out in the open – and that’s what we’ve done here.

More broadly, can we be comfortable with results based on national-level data rather than using data from individual multinationals? Here, there may be a sense of some convergence. Our estimates using data on US multinationals implied global tax losses annually of $130 billion. Scaled up from the rough US share of 20% in global FDI, and assuming all multinationals are equally aggressive to US multinationals, the extrapolated losses would be in the region of $650 billion. A global total of $500 billion does not seem inherently implausible then; and might perhaps suggest US multinationals to be among the most aggressive internationally.

We don’t think the methodology is perfect; nor of course, the estimates precisely accurate. But we hope that this is a valuable step in the ongoing process of assessing more closely, and responding more effectively, to this first-order global policy problem.

As is often the case, we conclude that there will only really be certainty on the scale of global profit-shifting when governments decide to require that multinationals’ country-by-country reporting must be made public. Now that the OECD has created a standard, based on the 2003 Tax Justice Network proposal by Richard Murphy, the compliance costs are effectively nil – and the accountability and revenue impacts likely to be large indeed. And in that vein, the work of Open Data for Tax Justice to bring together existing country-by-country data and demonstrate its value, continues. We welcome support there, and of course comments on the paper published today.

Read the subsequent article in the Journal of International Development “Global distribution of revenue loss from corporate tax avoidance: re‐estimation and country results” (open access).