Regional tax harmonisation is controversial, with compelling arguments for and against. Is it desirable? Or beneficial? And if so, to whom? We examine these and other questions in the context of the taxation of mobile money (MM) in the East African Community (EAC). The EAC – the historical leader in Africa’s MM market – is, in principle, committed to tax harmonisation.

What’s levied, and how do cross-country MM taxes compare within the EAC?

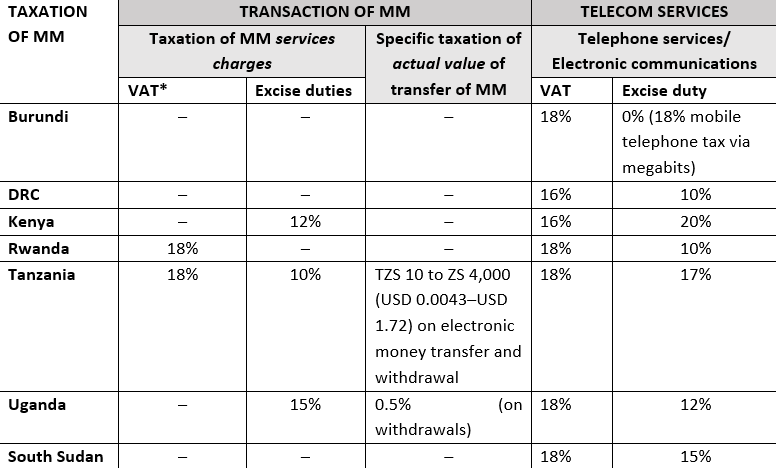

Consumers pay three taxes:

- value-added tax (VAT) and excise duties levied on transaction fees charged by MM providers;

- specific taxes on the underlying value of MM transactions; and,

- consumer taxes on telecom services and goods

As shown below, charges and rates are hardly harmonised, and are typically high. This high rate is not unique to the region: compared to general global trends, Africa as a whole charges relatively higher MM taxes. Might this inadvertently affect market development and efficiency, particularly investment by telcos (telecommunication companies)?

These divergent taxes and charges on MM could create regional trade distortions. Yet EAC governments show little sign of consultation or peer-to-peer learning.

Definitions and differences

While the provision of financial services is broadly exempted from VAT, their definition and scope differ between countries. In addition, although VAT is largely harmonised across the EAC, there are multiple country-specific exemptions – as well as variations – in rates. For instance:

- Tanzania levies 18% VAT on transfer fees payable to banking and non-banking institutions.

- Rwanda levies 18% VAT on fees for mobile banking when this service is provided by telcos.

Excise duties also vary widely in tax rate and bases, making it difficult to compare the tax burdens on MM. For instance:

- Kenya applies excise duties on fees for money transfer services (transfer and withdrawal) charged by telcos (12%).

- Tanzania applies excise duties on fees payable to telcos for money transfers and payments (10%).

- Uganda applies excise duties on fees for money transfers and withdrawals by telcos (15%).

The excise duty rate on MM fees in Tanzania and Uganda is the same for digital or traditional services. In contrast, at 20%, Kenya levies higher for money transfer services and other fees charged by traditional providers.

Specific taxes on the underlying value of specific MM transactions

The latest addition to the disparate array of national taxes on MM are the special taxes on the value of MM transfers:

- Uganda has applied a 0.5% tax on MM withdrawals since November 2018.

- Tanzania introduced a tax on MM transfer and withdrawal transactions in July 2021, which was decreased a year later in July 2022 to between TZS 10 and ZS 4,000 (USD 0.0043–USD 1.72).

According to Tanzania’s National Payment Systems (Electronic Money Transaction Levy) Regulations 2022, the scope of electronic MM includes “the transfer of electronic money from a user’s MM account to a user’s bank account, a user’s bank account to a user’s bank account, or a user’s bank account to a user’s MM account”. This extension to electronic money accessed by banking applications presumably seeks to level the playing field between banks and telcos. Previously, non-mobile based transfers transacted through banks were exempted, as were bank-to-MM wallet transfers. Levelling the playing field has resolved that mobile-based transactions were indeed more heavily taxed.

Consumer taxes on telecom services and goods

The new wave of taxes on MM does not seem to have brought convergence on how best to tax telecoms goods and services. Tax policies on electronic communications remain widely diverse. Burundi levies a specific tax on megabits, while Tanzania imposes a tax on airtime. These new levies on MM services could slow down rather than accelerate financial-sector development and expansion. Multiple taxes on telecom goods and services raise the cost of digital financial services (DFS), including MM. A notable exception is Burundi, where telephone communication is exempted from MM excise duties.

Corporate taxation of service providers

This blog post mainly dwells on the disparities of consumer-facing taxes, and not on the costs to service providers. Regarding corporate taxes, there is an appreciable degree of harmonisation:

- Except South Sudan (20%), telcos are subject to 30% on profits in all EAC countries.

- All countries charge licence and spectrum fees.

- In Kenya, telcos are subject to a special telecom tax.

- In Rwanda, telcos must contribute between 2.5% and 3% of turnover to Community-Based Health Insurance (CBHI), the universal health insurance scheme.

Growing momentum for legislative and regulatory harmonisation

All said and done, EAC’s tax framework is currently fragmented, contrary to goals for greater economic integration and harmonisation to reduce trade disputes and disruptions.

In the absence of the desired regional integration, partner states compete fiercely to attract investment, using blunt-edged corporate exemptions and tax holidays. Each national legislature still determines specific taxes on single MM services. Without fiscal coordination on MM taxation, EAC states are likely to miss opportunities to optimise investment and economic growth that could come from leveraging the power of increased EAC integration to remove tax distortions, mitigate the negative effects of tax competition, and boost balanced regional investment.

In November 2020, during the 48th general meeting of the Commissioners of the East African tax authorities, there was an agreement to develop a joint strategy for the taxation of the digital economy through regional tax harmonisation. The EAC has a strong legal basis for harmonisation of tax policies for intra-EAC MM transfers, and across sectors.

Potential for convergence of mobile money taxation across the EAC

An avenue for gradual convergence of MM taxation is to act on the EAC’s aspiration towards integration, with a regional holistic vision rather than individual, uncoordinated, national positions. Through regulatory collaboration, undergirded by a deeper analysis of impacts of taxes on DFS and consultation with providers and users, partner states could work towards a coordinated and consistent approach on MM and DFS. A fair level of taxes levied could enhance financial inclusion among EAC citizens. It would potentially also provide an operational model to tackle broader issues such as wasteful and harmful tax competition for foreign direct investment.

Targeted evidence-based research is needed to secure government revenues and other economic-growth considerations, in order to define harmonised policies that are politically feasible, and that create incentives.

A logical starting point for national policymakers and officials would be to harmonise tax bases rather than rates. In the EAC, as in the European Union, tax rates can remain different for as long as necessary for the stage of development and national cultural traditions and critical considerations, provided there is no outright discrimination. This process could be kick-started by an EAC-wide review to determine an optimal tax approach for companies and consumers, eliminating tax exemptions, and through policy that encourages healthy competition.

The EAC should agree on a regional, holistic approach in defining uniform and transparent tax bases – regardless of the rate – for service providers (on revenues) and consumers (on fees and/or values of the amount transacted). Without better coordination on taxation of MM services, the region will struggle to optimise outcomes for its citizens, its economy and inbound investment.

If the EAC succeeds at regional tax harmonisation of MM, West Africa would learn valuable lessons. These lessons are opportune as countries like Ghana and Nigeria introduce consumer MM taxes.

Acknowledgement: The author would like to thank Chris Wales, Philip Mader, Laura Muñoz, and Mary Abounabhan for their valuable suggestions. The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author only. This blog post was edited by Njeri Okono.