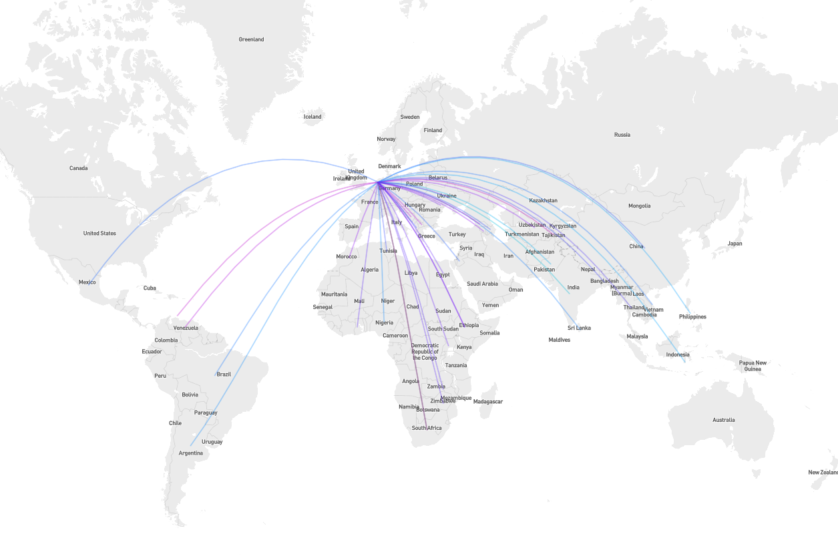

A vast network of tax treaties to facilitate investment

When comparing countries’ foreign direct investment, you would expect the world’s largest economies to top the list. However, in this world, where businesses structure their international investments following the logic of tax minimization, the Netherlands sits firmly at the top, along with the United States and Luxembourg. A major reason for this is the friendly Dutch tax environment, specifically constructed for international business and enabled by a vast network of tax treaties (nearly 100 in total). These are popular among international investors, as they minimize the taxing rights both governments can claim over bilateral investments.

An important taxation right is the withholding tax over outbound passive income payments, such as dividends, interest and royalty payments. The Netherlands has succeeded in lowering withholding tax rates in its tax treaties with other countries, sometimes even to zero. It has faced significant criticism for its key role in international tax avoidance structures, as it undermines the ability of other countries, especially developing countries, to collect sufficient taxes.

Dutch tax treaty policy in relation to developing countries

The Netherlands set out its tax treaty policy in a special ‘Memorandum on Tax Treaties,’ which was last altered in 2011, but earlier this year a new version was presented to the Dutch Parliament. Although the Netherlands mainly follows the OECD tax treaty model, it has set forth specific deviations, including one regarding tax treaties with developing countries. Both the 2011 and 2020 versions state that the Netherlands will “show understanding towards developing countries, for instance, for requests for an expansion of the concept of ‘permanent establishment’ or for relatively high withholding taxes.” In a parliamentary debate, it was also affirmed that “the Netherlands is prepared to agree to higher withholding taxes than in relation to more developed countries, with the understanding that the Netherlands wishes to achieve a result more or less equivalent to that in the treaties of that developing country with comparable more developed countries.”

But has this been put into practice?

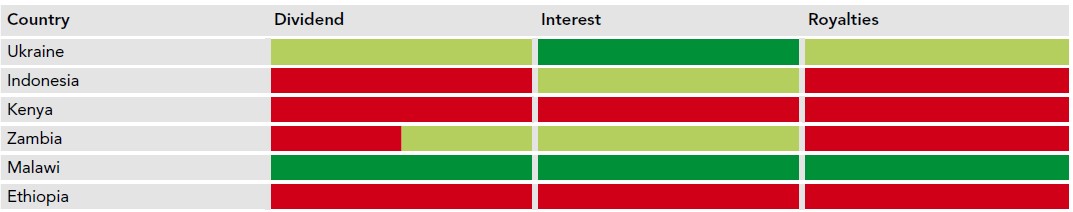

The Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (SOMO) recently published a study assessing whether Dutch tax treaties have, since the 2011 memorandum, provided more taxation rights to developing countries. Our study examines the six tax treaties the Netherlands negotiated or renegotiated with developing countries since 2011. These are with Ukraine, Indonesia, Kenya, Zambia, Malawi and Ethiopia. The treaties with Kenya and Malawi have been signed, but not yet ratified. The withholding tax rates concluded in the treaties for dividends, interest, and royalties are shown in the table below.

| Country (year of signature) | Dividend (%) | Interest (%) | Royalties (%) |

| Ukraine (2018) | 5 | 10 | 5/10 |

| Indonesia (2015) | 5 | 10 | 10 |

| Kenya (2015)* | 0 | 10 | 10 |

| Zambia (2015) | 5 | 10 | 7.5 |

| Malawi (2015)* | 5 | 10 | 5 |

| Ethiopia (2012/2014) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

*Signed, but not yet ratified

We compare the withholding rates negotiated in these treaties with the Netherlands to those negotiated between the same six countries and other OECD countries, of which there are a substantial number: Ukraine: 31, Indonesia: 25, Kenya: 8, Zambia: 12, Malawi: 5, Ethiopia: 10. The table below shows whether the withholding tax rate in the Dutch treaty is higher (dark green), equal (light green), or lower (red) than the average rate with OECD countries. For four of the six treaties, at least one of the withholding tax rates negotiated with the Netherlands is lower than the OECD average. The treaties with Kenya and Ethiopia appear especially inconsistent with the 2011 memorandum.

By examining the explanatory memoranda for each treaty, we found that in many cases the Dutch government had explicitly aimed to secure low(er) withholding tax rates. Therefore, it seems that the Dutch government has not consistently followed the principle it put forward of agreeing to higher rates in order to achieve results that are more equivalent to those negotiated with comparable developed countries.

Our study calls into question the Netherlands’ commitment to negotiating fairer tax treaties with developing countries, and to halting the international race to the bottom. It appears to be more concerned about maintaining its large network of advantageous treaties that enable international investors to avoid taxation.